We have always known that the brain is vital in the experience of pain. There may be no truer statement regarding this notion than “No Brain, No Pain”. While we know that the brain is involved in every pain experience, it remains our most mysterious organ. While there is still a tremendous amount to learn, especially for pain scientists, we have gained an incredible amount of knowledge in recent years. The use of advanced imaging, for example the functional MRI (fMRI), has allowed us to visualize areas of the brain that are activated in different circumstances, for example the experience of pain.

Through research we have learned that certain areas of the brain always light up when someone is in pain. These activated areas are the same no matter the reason why someone hurts. They could have an acute episode of back pain, have stepped on a nail, have fibromyalgia, broke their wrist, or sustained a nasty papercut between their index and middle finger. These areas of the brain communicate with each other, forming a neuronal circuitry that often is referred to as the ‘pain neuromatrix’.

In addition, these brain areas have other jobs to do besides pain. When the brain is occupied by pain, these areas are affected. When someone is in chronic pain, these areas often become hijacked by pain, and the individual suffers.

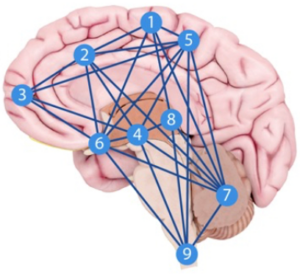

The typical pain neuromatrix, with individual brain functions and ramifications for chronic pain, include the following nine areas.

- Premotor/Motor Cortex. These areas plan, organize and execute movement. When pain comes along, these areas get hijacked and movement becomes altered. This is a reason why movement is off in people in pain.

- Anterior Cingulate Cortex. This area deals with focus and concentration. When pain comes along, this area becomes hijacked. Patients may complain of a ‘fog’, having difficulty concentrating, becoming mentally tired. This is a reason why people in pain (e.g. fibromyalgia) are often in a ‘fog’ and can’t concentrate or focus.

- Prefrontal Cortex. This area deals with problem solving and memory, analytical tasks and numbers. When this area gets hijacked by pain people have difficulty with numbers, analytical tasks and memory.

- Amygdala. This area deals primarily with fear and fear conditioning. It analyzes threats. When this area gets hijacked by pain, we may have a heightened sense of fear and threats (not just about pain) become overblown. In a clinical sense, patients may have elevated fear when asked to do relatively simple tasks and exercises. In addition to fear, the amygdala is involved in addiction and addictive behavior.

- Sensory Cortex. This area deals with sensory discrimination, for example distinguishing between a hand and a foot or between your right hand and left hand. When pain hijacks this area, we may have difficulty identifying body parts.

- Hypothalamus/Thalamus. These areas deal with stress responses, body temperature, how much we eat, how food tastes, autonomic regulation, and motivation. When this area gets hijacked by pain many of our body functions suffer.

- Cerebellum. This area of the brain is involved in fine motor control, balance, and proprioception. When this area gets hijacked by pain, movement and balance are affected.

- Hippocampus. This area deals with memory, especially short term memory, as well as spatial recognition and fear conditioning. When this area gets hijacked by pain, memory is affected.

- Spinal Cord. While not technically an area of the brain, this region of the central nervous system deals with modulating incoming signals from the body, for example increasing or decreasing ‘danger signals’ from our tissues, which often become pain. When this area gets hijacked by pain, signal modulation is affected.

No matter the reason for your pain, you’ll use these nine areas of your brain. As far as understanding the effects of pain on the sufferer as a whole, this information is of incredible importance. We usually think of pain as being related to the affected body part, but our current understanding of pain has shed a ton of light into the role of the brain. This information also helps with the management of pain, and we now know that if we can change the threat associated with pain, we can decrease pain in many patients. Changing the threat involves knowledge about pain, which involves understanding the role of the brain in a pain experience. As far as the treatment of pain goes, whether be from a chiropractor, physical therapist, primary care physician, orthopedic surgeon, etc. this information is a game changer. The brain, especially the nine areas listed above, can increase or decrease the amount of pain someone feels.

Source: The Webinar ‘Warning Signs and the Perception of Pain’ by Adriaan Louw, PhD, PT, CSMT accessed from medbridgeeducation.com